The Skin of the World

PROPOSITIONS FOR A CINEMA OF RESONANCE

In the context of Courtisane Festival 2024 (Gent, 27 – 31 March 2024) with the support of KASK & Conservatory / School of Arts. Curated by Stoffel Debuysere in the context of the KASK research project Echoes of Dissent.

“The skin of the world… always floating and responding to the thrusting of the world’s breezes, breaths and gusts. In all respects, it is the powerful and fragile resonance of all that arouses a form or tonality of existence.” (Jean-Luc Nancy)

To resonate: re-sonare. To sound again — with the immediate implication of doubling or ghosting, assuming a haunting spectrality. Resound, rebound, refrain, return: sound sent back to us, reflected by surfaces, diffracted and refracted by edges and curves. Sound amplified, swathed in an acoustic ambience that transforms it. Sound enhanced and prolonged by its passing through a certain field or structure. Sound reaching out into the distance, suspended and straining between arrival and departure. Sound propagating itself, configuring a sense and a presence in the world. But to resonate is also to reverberate and reciprocate, to correspond and respond to something or someone other. Furthermore, to resonate is to remember, to evoke the past, to activate its latent potentialities and frequencies. It is also a mode of relation that allows for non-sequential forms of exchange and synergy, accommodating affective affinities and formless formations.

Resonance embraces a multitude of different meanings. Or rather, it is actualised and expanded in a wide range of different phenomena and circumstances. How can we think through the notion of resonance in or as cinema? What would happen when we consider cinema as a territory upon which resonance may unfold?

This programme aims to formulate a set of tentative propositions, or hypotheses, on what a “cinema of resonance” could be — seeking what is grounded in resonance, neither showing nor telling but sounding and resounding. A programme populated by glossic and phonic traces received and amplified across time, conjuring up forgotten histories and haunting memories; chants, murmurs and scansions reverberating through the stillness of desolated spaces and catastrophized places; songs and stories echoing and expanding into symphonic movements and sonic geographies. A programme that tries to consider resonance not only as form or content but also as method, involving a practice of pairing and configuring works that relate in ways that are not necessarily causal, historical or geographical, let alone inevitable, but that nevertheless are there. A programme as an accommodating resonance chamber that allows, but does not compel, a process of mutual oscillation between films that somehow speak to one another. It is up to us to lend them our ears.

Thanks to all the filmmakers and distributors involved, Ricardo Matos Cabo, Erika Balsom

In the context of the research project Echoes of Dissent (KASK & Conservatory / School of Arts Gent)

——

THE SKIN OF THE WORLD 1

30 MARCH, 2024 – 19:00

SPHINX CINEMA 3

Listening to the Space In My Room

Robert Beavers, US, 2013, 16mm, 19′

“The life of a sound should inhabit the film frame,” Robert Beavers wrote in one of his numerous notebooks. Of all the astonishing films in his singular body of work, Listening to the Space in My Room is perhaps the film that manifests the life of sounds in the most evocative way. Between 2002 and 2012, Beavers lived on the ground floor of an old house in Zumikon, a quiet Zurich municipality, just underneath his landlords, Cécile and Dieter Staehelin, a retired doctor and a cellist, respectively. This film is a lyrical ode to the Staehelins and to life in this long-shared place, as well as an exploration of resonance as an acoustic signature of a space, connecting sound and space through the element of time. Throughout the film, Beavers articulates zones of permeability — between floors, between garden and interior, between subjectivities. Cello tones and birdsong join the crackle of creaking floorboards and the muffled sounds of footsteps and conversation, extending the meditation on the acoustics of shared inhabited space. “At about midpoint in the film we hear the sound of rain first introduced with black leader and then accompanying a pan as the rain falls on the garden and elephant leaves. This rich and complex sound- scape breathes with life and exudes a quality which opens the soundtrack to the outside — to that which is traditionally outside of music (noise) and to the world beyond the visual space of film.” (Luke Fowler)

“Imagine someone boiling down all the impermanent sensations, routines, memories, and emotions that make a home a home into an intensely flavorful reduction, and you begin to understand Beavers’ stunning film. He and his housemates are crystallized at work: the camera sways with the hands of an older man bowing his cello; observes an older woman tending her garden from inside the darkened house; mirrors Beavers himself examining individual frames of film to stage his somatic cuts. The intricately interlaid tracks of sound and image do not abide any standard measure of continuity, and yet there’s something immediately comprehensible in this exquisitely tuned song of the body in space.” (Max Goldberg)

Die Reise nach Lyon (Blind Spot)

Claudia von Alemann, DE, 1981, 16mm to DCP, 112′

2K digital restoration by Deutsche Kinemathek

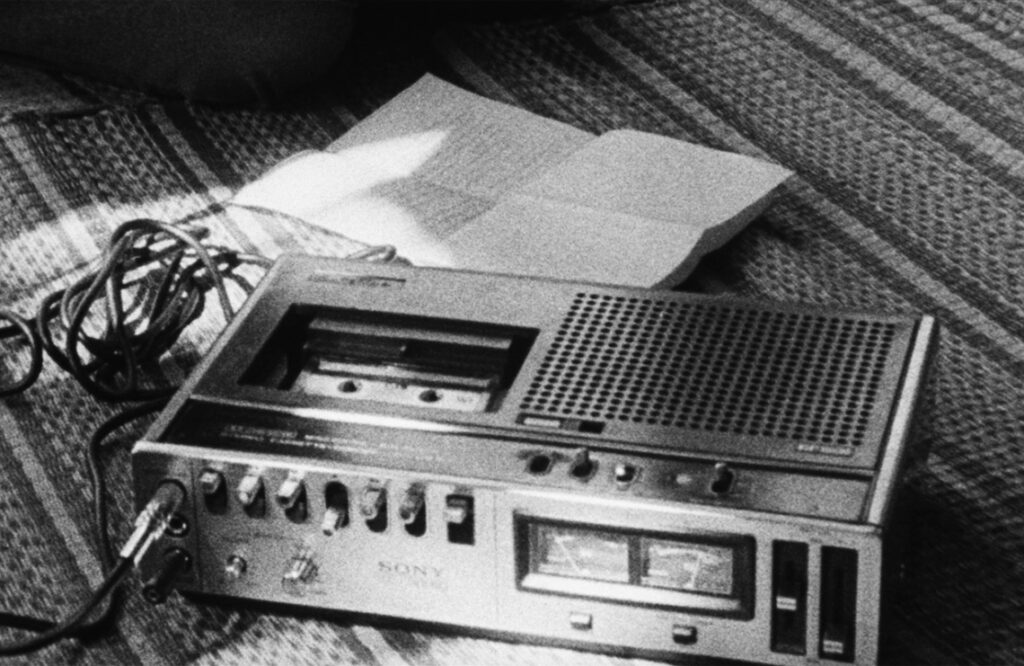

Elisabeth wanders the sleepy streets of Lyon, following in the footsteps of socialist and feminist writer Flora Tristan. Carrying with her the writer’s diary and a tape recorder, she tries to reconstruct what Tristan might have felt when she walked the same streets, shortly before her death, at 41, in 1844. Filmed before Lyon’s Italianate facelift and its listing as a World Heritage Site, this remarkable exploration of feminist history portrays a working-class city where traces of the past persist, the leprous facades revealing wrinkles that hark back to the Canut revolts of the 19th century and the roundups during the Second World War. But it is not so much the image that marks this film as it is the sound. It is surprisingly present and all the more vivid because it plays on scarcity, somewhat like the image yet in an even more radical way. Everything happens as if the city were an echo chamber, as if each scene were a sounding board for everyday sounds floating between strangeness and familiarity, past and present. The violin, which Elisabeth plays in the final scene as a resolution to her search, makes her grasp the meaning of resonance, which is first of all that of her footsteps in the city. “I could hear the sound of my own footsteps. I moved and my steps echoed through the street. The echo of Flora’s footsteps, a century and a half later: the echo of her passage.” By listening attentively, Elisabeth is able to recognize, in the humblest of sounds, the strongest of resonances: the imprint of the past underneath the ech- oes resounding in the present.

“In Die Reise nach Lyon, a woman historian, fascinated by the diary kept by Flora Tristan during the last few months of her life, refuses the traditional way of ‘looking’ at history and gets caught up in a complex, multi-layered pattern of reverberations. History and ‘her’ story become a network of resonances. One life/ voice imprints in another. The process of social change, instead of being read by academic detectives in stuffffy archives, resound in a space between a sound and its similar echoes. A visually fascinating fifilm which is nevertheless one of the few real sound fifilms ever made.” (Paul Willemen)

Followed by a conversation with Claudia von Alemann

Supported by Goethe-Institut Brüssel

——

THE SKIN OF THE WORLD 2

31 MARCH, 2024 – 14:45

SPHINX CINEMA 3

In der Dämmerstunde – Berlin – de l’aube à la nuit

Annik Leroy, BE, 1981, 16mm to DCP, 67′

Newly digitized version

In some ways reminiscent of Claudia von Alemann’s Die Reise nach Lyon, which came out in the same year, Annik Leroy’s debut film follows the filmmaker as she wanders through the ghostly twilight zones of Berlin in search of a past that no longer exists. Another act of remembering as spatial experience, a journey that traverses space to become, in time, a peregrination. “With this film I try to retrace my journey, my story through the ruins, neighbourhoods, and streets of Berlin. I filmed the dialogue that took place between the city and myself, the wanderings in the old neighbourhoods (Moabit, Kreuzberg, Wedding), places where you can still find most of the traces of the past, or rather what’s left of them.” Shot in a time seemingly far from today’s neoliberal explosion in Berlin, the film depicts the city’s crumbling surfaces and desolated wastelands as the silent witnesses of a tragedy that has left deep wounds. A tragedy that finds resonance in literary and musical fragments borrowed from the work of Gottfried Benn, Else Lasker-Schüler, Witold Gombrowicz, Peter Handke, Gustav Mahler and Richard Wagner. From the crunching sounds of Leroy’s footsteps on the snowy shores of the Landwehrkanal, to overheard murmurations of faceless voices on the U-Bahn train and loudspeakers announcing the end of the line, the film renders the city as a vast cavern of sound, impregnated with present absences and absent presences that haunt its phantasmic landscapes.

“We discover the sounds of a claustrophobic city and get lost between loudspeakers announcing dead-end streets. We overhear the constant murmur of foreign languages trying to find a voice in a wasteland of asphalt, street lights and the Berlin Wall, marked by darkness and scars of the past. ‘Just don’t stare at a wall’, declares Gombrowicz, and the film moves on. Leroy searches for traces of World War II as well as for love and humanity. It’s a contradiction, but it contains the darkened German soul: how to make an emphatic image of this place?” (Patrick Holzapfel)

Resonating Surfaces

Manon de Boer, BE, 2005, 16mm to digital, 39′

Newly digitized version with 5.1 audio mix

Cries of death open Resonating Surfaces: the cry of Lulu from Alban Berg’s eponymous opera, and that of Maria, a character in Wozzeck, another opera by the same composer. In the resonance of these vocal timbres, distinct degrees of life-affirmation arise, even and above all in the face of death. Brazilian psychoanalyst Suely Rolnik wrote: “It is a recognition that, even in the most adverse situations, it is possible to resist the terrorism against life, against its desiring and inventive potency, and to stubbornly go on living. Together, Lulu’s and Maria’s cries convey this lesson and contaminate us.” This sonic experience lies at the heart of Resonating Surfaces; an experience that launched a personal movement of liberating effect, de-anesthetizing the marks of the trauma caused by dictatorship and imprisonment. This experience is conveyed by Rolnik, whose story we hear unfolding throughout the film, as the use of the voice gradually shifts from timbre to language. Made in close collaboration with violinist and composer George van Dam, Resonating Surfaces situates Rolnik in the context of the sounds and sensations of São Paulo, her native city, as well as the intellectual atmosphere of 1970s Paris, the city of her exile. In its open and subtle orchestrations of the spaces between image, sound and voice, the film’s formal inventiveness seems to resonate with Rolnik’s appeal to open our resonant bodies to the forces of the world’s otherness and, above all, to tune our hearing to the affects that each encounter mobilizes.

“One could say that de Boer’s films explore the contradictory relation between perception (based on the recognition of preordered forms) and sensation (meaning the open-ended contact with the flux of physical phenomena) — of the kind that Suely Rolnik also discovers in aesthetic experience… De Boer recently cited Rolnik’s distinction between ‘the sensation of the ‘world-as-force-field’’ and the ‘perception of the ‘world-as- form’’, in order to identify what is at stake in her films. Responding to the kinship between her own artistic sensibility and Rolnik’s philosophical approach, de Boer made Rolnik the subject of Resonating Surfaces, the work that best reveals the political stakes of de Boer’s art.” (TJ Demos)

Followed by a conversation with Annik Leroy and Manon de Boer on sound and resonance in their work

——

THE SKIN OF THE WORLD 3

30 MARCH, 2024 – 16:00

SPHINX CINEMA 3

Signal — Germany on the Air

Ernie Gehr, US, 1982, 16mm, 34′

Ernie Gehr, the son of German Jewish émigrés, might have called Berlin home had fascism not tragically intervened. The film takes its title from the Wehrmacht propaganda magazine of the same name. Its opening shot is backgrounded by a cropped view of the magazine’s cover. The explicitness of this reference comes as somewhat of a feint, as Gehr’s approach to history is otherwise oblique. Signal unfolds in a site of little dramatic consequence: an anonymous intersection, somewhere, we glean from interspersed street signs, on the Rheinstraße. Creamsicle trash cans touting the slogan “Berlin…ICH MACHE MIT” (“Berlin…COUNT ME IN”), locate us in Germany’s capital. Yet Gehr withholds further orientation. The intersection’s nondescriptness repels attempts to impute significance. Gehr couples his crystal-like montage with segments clipped from a cheap German radio and street sounds that never quite align with what we see. Heels clack, buses stall, and conversations transpire over scenes emptied of all but asphalt and low-rises. The faint sound of ghostly and multilingual voices compounds our sense of dislocation. The soundtrack constantly points to an ethereal absence, not only emanating from other parts of the world, but also from Berlin’s continually haunting past. “Gehr films the streets as if they were the scene of a crime,” wrote J. Hoberman in his review of the film. Gehr edited Hoberman’s assessment: “there was,” he said, “no ‘as if’ about it.”

“Signal — Germany on the Air uses empty camera movements, anonymous citizens, and the ubiquitous radio to portray an absent subject, the filmmaker and survivor on a street in Berlin where he no longer lives. An alternative future, another world, opens in the space where I am not, where I might have been. Others are witness to my invisibility, to my absence in advance, and to my return to the place where I am not, or no longer am. The subject is spectral, a trace that marks an absence in advance: An absent, reflected subjectivity, invisible to the film, an autobiograph under erasure.“ (Akira Mizuta Lippit)

still/here

Christopher Harris, US, 2000, 16mm to DCP, 60′

2K digital restoration by the Academy Film Archive

still/here is a meditation on the vast landscape of ruins and vacant lots that constitute the north side of St. Louis, an area populated almost exclusively by working class and working poor African Americans. On a basic level, the film constructs a documentary record of the blight and decay of that part of the city. still/here is, for the most part, not an overt assessment of social injustices, but the politics of class and race within American society are integral to the film. In still/here, the ruins are emblematic of an unimaginable absence at the core of much of the African Diaspora’s experience in North America. From the countless Africans lost in the Middle Passage to the lost future generation of unborn descendants of those that perished during the voyage, to the loss of family and loved ones that were sold away during slavery, absence has been and continues to be a fundamental feature of the African-American experience. But how, in an image-based medium such as film, does one represent absence? “With still/here, I attempt to engage this question by developing a vocabulary of absence. To that end, the film acknowledges the limits of representation and proceeds through a series of visual and aural breakdowns, erasures, contradictions and gaps. It does not use the documentary power of film to recuperate a sense of closure but instead dwells within the space of rupture occasioned by the presence of a profound absence.” Fixing our gaze on derelict cinemas, fading billboards and crumbling facades, we are rarely shown a human being — but their presences haunt the dirgelike soundtrack, abound with unanswered phones, eerie footsteps, closing doors, chat show phone-ins and dripping taps.

“still/here’s urban scene is deserted, and it is filled with the aural remnants of the African American community that might have once inhabited the now abandoned houses and made the barren street feel like a neighborhood. still/here is hybrid and contradictory: ethnography without people; a personal essay without a human face; a documentary without neither a setting nor a clear thesis. Harris’s film shows a specific place turned into a nameless, almost borderless space and then monumentalized as a metaphor. Harris’s images invite the audience to reimagine the abandoned lots, absented houses and discarded equipment as not ruined but ruins.” (Terri Francis)

On the Battlefield

Little Egypt Collective, US, 2023, 16mm to DCP, 13′

In the southern Illinois region of Little Egypt, a sound recordist revisits the flat fields where once stood Pyramid Courts — the housing projects that formed the heart of the Black community of his hometown, Cairo. His mic gathers sonic ephemera of past, present and future within the grasses, trees and skies. Kids play, birds flock, a grandmother and granddaughter burn sage for protection from evil spirits, and an official who oversaw the projects’ closing reflects on its psychic toll. Throughout, a 1970 private release LP by the United Front of Cairo, a Black power movement led by Rev. Dr. Charles Koen, guides the sound recordist — and us — on a search for connections across struggles for liberation, near and far. On the battlefield, these voices march towards resurgence. As the first Little Egypt Collective release, On the Battlefield is an overture celebrating the joy and power of Cairo, a town famous for confluences and collisions: between the North and South, the Mississippi and the Ohio rivers, and Black liberation and white supremacy. The film offers an aperture of encounter, resistance and inspiration, and invites audiences into these muddy histories and potent spaces. (Berlinale)

“Sound is the inspiration for this film. Over the past seven years of our collaborative work in Cairo, we have been focused on sound recording as a means of attending and listening to the stories animating the community and landscape. Thus, we have an incredible library of sounds from the Little Egypt region: environmental sounds of bayous, farmlands, marshlands; industrial sounds of river barges, railroads, the local Bungee’s mill; stories and ambiences from local communities; as well as archival sounds, such as the On the Battlefield LP, which was produced by Cairo’s United Front and serves formally as the structure for this first film… As we all edited together, we understood that On the Battlefield poignantly traverses across past, present, and future, and carries a message that spans to many other landscapes and communities within the US, and beyond.” (Lisa Marie Malloy)

Little Egypt Collective is Theresa Delsoin, Lisa Marie Malloy, J.P. Sniadecki, Ray Whitaker with Rachel Burns, Zah-Karri Levy, Towanda Macon, Kyrie Wright.

——

THE SKIN OF THE WORLD 4

30 MARCH, 2024 – 13:30

SPHINX CINEMA 3

Kere mattu Kere (The Lake and The Lake)

Sindhu Thirumalaisamy, IN, 2019, DCP, 38′

Filmmaker and composer Sindhu Thirumalaisamy grew up in Bangalore, India, a city that used to be known for its pleasant climate and green spaces. Today, Bangalore’s wetlands are polluted with sewage and waste to such an extent that they produce spectacular foams — in the artist’s words: “bubbles of wealth surrounded by pools of neglect.” The Lake and The Lake responds to a media-driven crisis around these phenomena by offering a representation of one particular lake, Bellandur, as a toxic commons. The lake is toxic in both senses of the word: poisonous to the living beings that inhabit it and high-risk in economic terms. Nevertheless, it remains a space of commoning for various people whose labour sustains the city’s development. Moving through the peripheries of Bellandur lake alongside fishing communities, waste workers, foragers, security guards, street dogs, and children, the question arises: what constitutes a ‘nature’ worth protecting? On the soundtrack, the landscape is washed over with acoustic and acousmatic voices, devotional music, religious speech, jet engines, rifle shooting sessions, children playing, the rhythms of work, the chatter of hundreds of birds and insects. “Like much of my work with ambient sound, these moments are about presence, about dwelling in common…I treat some sounds as residual echoes, mimicking my experience of the music that echoed over the surface of the lake. When music reached me from across the lake, it would be hollowed out with only a faint traces of its melody. I recreate this effect of the sonic residue in some segments of the film, producing an uncanniness that I associate with the lake.”

“Patient frames lead us along the shores where we can examine a square metre of dirt, a posse of lounging dirt dogs, plants whispering in the breeze. The artist traverses the city’s fringe, the liminal edge, as conversations with friends and strangers, experts and neighbours weigh in, along with a bevy of carefully crafted field recordings… In place of a polemic, a broadsheet, or an overview: there is a search. An attuning. A being with. Little surprise that the artist has a sound practice, not only because her tracks are so rich, but because this is a movie that invites us to listen to her listening. Such a deep and unexpected pleasure. As if there was time for that too.” (Mike Holboom)

Recollection

Kamal Aljafari, PS, 2015, DCP, 70′

For many years, Kamal Aljafari has been collecting Israeli and Hollywood fiction films shot in his hometown Jaffa. These are films in which Palestinians are absent, yet they exist at the edges of the frames, visible only in traces and shadows. Further preserved in this archive is a city; its gradual dismantling over the decades chronicled film by film. From the footage of dozens of films, Aljafari has excavated a whole community and recreated the city from his youth, before its destruction by colonization and prior to the settlement projects. “Though out-of-focus, half-glimpsed, I have recognized childhood friends, old people I used to say good evening to as a boy… My uncle. I erased the actors. I photographed the backgrounds and the edges and made the passers-by the main characters of this film. In my film, I find my way from the sea, like in a dream. I walk everywhere, sometimes hesitant and sometimes lost. I wander through the city; I wander through the memories. I film everything I encounter because I know it no longer exists. I return to a lost time.” The spectral politics of Recollection is accentuated by its soundtrack, recorded in collaboration with sound artist Jacob Kirkegaard, which brings to life the ghosts lingering beneath the city surfaces. With the help of contact microphones, vibration sensors and hydrophones, they not only captured the hidden sound layers resonating in the walls but also in the ocean, which for Aljafari symbolizes desire. “The Israeli government and the municipality of Tel Aviv destroyed Jaffa. They threw the homes they destroyed into the sea. But every year, in the winter, when the sea rises, it throws part of these homes back onto the shore. The Tel Aviv municipality collects them, throws them back, but the ruins return. Every year the sea brings them back.”

“In Recollection, freedom is experienced in ‘the sound of the ocean… the echo you can hear outside but recorded from inside the wall. Life buried beneath, inside the sea’. As the images move slowly, other times brusquely, from a silhouette to a shadow, a sliver of the port city of Jaffa to another, the sound moves us into the present unearthing a past. We begin to see the ruins as breathing bodies. We see the place Palestinians have lived in and have been exiled from. And gradually we are brought face-to-face with history, with destruction. The phantoms stare at us. The filmmaker ‘frees the image’, an act he calls ‘cinematic justice’.” (Nathalie Handal)

Followed by a conversation with Kamal Aljafari

——

THE SKIN OF THE WORLD 5

29 MARCH, 2024 – 14:30

KASKCINEMA

Get out of the Car

Thom Andersen, US, 2010, 16mm, 34′

Thom Andersen’s Get Out of the Car is a response to his earlier Los Angeles Plays Itself, considered to be his signature film. He described the latter as a “city symphony in reverse” in that it was composed of fragments from other films which are read against the grain to bring the background into the foreground. Convinced that Los Angeles has not been well served by these films, Get Out of the Car grew out of an obsession with making a proper city symphony film of his hometown. It concentrates on small fragments of the cityscape: billboards, advertising signs, wall paintings, building facades and unmarked sites of vanished cultural landmarks, while the soundtrack brings together an impressionistic survey of popular music made for the most part in Los Angeles from 1941 to 1999, with an emphasis on rhythm’n’blues and jazz from the 1950s and corridos from the 1990s. “Get Out of the Car began as a little study of distressed billboards, which was an intentionally dumb idea. But from there it made sense to go to other kinds of signage, murals, some rundown buildings. Almost all the music in the film is either Latino or Black in origin. The music of Los Tigres del Norte, for example, expresses the feelings of indocumentados. That also says something about the history of Los Angeles and where it is now. It ended up being a movie about immigration as well as Black culture in the city. Most of the things that we filmed in Get Out of the Car are gone now. The murals are pretty much all destroyed. There’s nostalgia there, but it’s not something I’m going to apologize for.”

“Get Out of the Car pays tribute to the unheroic, the overlooked and the disappeared… Andersen asserts that his is a ‘militant nostalgia’, not a passive one. By resurrecting the overlooked, he offffers an alternative story of the city he’s lived in for decades, rife with political as well as aesthetic motive. All the illusion and stagecraft has been stripped away, leaving empty lots and bare scaffolding — a city symphony in a minor key.” (Lyra Kilston)

Xiao Wu (Pickpocket)

Jia Zhangke, CN, 1997, 16mm to digital, 108′

4K digital restoration by Martin Scorsese’s The Film Foundation / World Cinema Project and Cineteca di Bologna

The films of Jia Zhangke depict a China moving from communism to (hyper)capitalism, a rural world slowly entering the urban age, an industrialized cityscape turning to neon bars and Internet cafes, and an ancient, enclosed society looking to join the global market. His heroes and heroines are those left behind in the transition, struggling to keep up with the current of China’s transformation: disaffected youth, small-time crooks, artists, sex workers. Zhangke’s unsurpassed attentiveness to the texture of quotidian life amid a society in flux is reflected in his remarkable use of sound, which emphasizes texture over clarity, and discordant noise over clean sonance. This taste for the dissonant and gritty, against the grain of today’s cinematic sound design, is nowhere as pronounced as in his debut film, Xiao Wu. It tells the story of pickpocket Xiao Wu, who drifts aimlessly through the streets of the small town of Fenyang. In his aim to capture the sonic environment of his hometown, Zhangke, together with his loyal sound designer Zhang Yang, produced a disorientating acoustic space filled with disjointed layers of street noise and popular tunes emanating from karaoke bars, street tweeters and novelty lighters, merging into a great cacophony of alienation. “Working with sound allows me to reconnect with the empty space of traditional painting, by appealing to the viewer’s imagination. For each of my films, I have therefore taken great care to create this relationship between the figuration of the filming locations and the sound space. In Xiao Wu, I chose to combine the image with the sounds of bicycles coming and going on the road and shop loudspeakers — which at the time were replacing those that used to broadcast political slogans: for me, these sounds document the China of the late 1990s.”

“Noise in Xiao Wu is not a negative presence. It reinforces the thereness of Zhangke’s Fenyang, the inner and outer lives of his characters. Noise is articulate, just as it is in the cacophonous zones of cities around the world. Who knows if it was modernity en masse that constituted the vulgar soundscape for RM Schafer when he was predicting sonic doom in 1977… But if modernity is vulgar, what then is refined? The absence of sound, one might guess: a library, a Buddhist temple, a suburb, death. Aesthetic value judgements and speculations aside silence is, well, silent. Noise on the other hand, is fifilled with information. Noise speaks, and in the Fenyang of Xiao Wu it never shuts up. Well then, let’s listen to what it is saying.” (Morgan Quaintance)

Introduced by Morgan Quaintance

——

THE SKIN OF THE WORLD 6

28 MARCH, 2024 – 11:00

SPHINX CINEMA 3

Lost Sound

John Smith & Graeme Miller, UK, 1998, video, 28′

Sharing an interest in synchronicity and chance encounters, film artist John Smith and sound artist Graeme Miller worked together on Lost Sound: a sonic reconstruction of their East London neighbourhood from cassette tapes they found discarded in the street. From sounds found hanging from trees like a mistletoe, from lampposts and awnings like the flotsam of an impossible high tide or blown by a breeze saturated with radio waves and mobile phone signals, Smith and Miller make a modern tangleweed of magnetic tape that sings its discarded memories. Bringing together characteristics of a sociological quest, a light-hearted form of situationism and a simple exercise in the art of the objet trouvé, the work explores the potential of chance. It creates an enthralling audio-visual cartography by building formal, narrative and musical connections between images and sounds that are linked by the random discovery of the tape samples. “A lyrical and poignant response to the urban environment, Lost Sound depicts the city as a disparate and fragmented series of personal histories. A sense of migration, loss and displacement seeps through upbeat soundtracks from sunnier climes.” (Helen Legg)

“The resulting video is a pure process piece — whatever music is playing on the soundtrack is that found on the fragment of tape that appears on the screen. The formality of the idea is undercut by the emotive power of the found music (and John stretching his own rules in the editing). John, who had always been suspicious of lush soundtracks, had found an excuse to use passion, albeit in a rigorous way. It was as if any emotion he wanted to feel (but was too embarrassed to deliberately express) could be discovered abandoned out on the street, emotion as a found object.” (Cornelia Parker)

Dogfar nai mae marn (Mysterious Object at Noon)

Apichatpong Weerasethakul, TH, 2000, 16mm to DCP, 83′

2K digital restoration by the Austrian Film Museum and Martin Scorsese’s The Film Foundation / World Cinema Project )

Inspired by the surrealist procedure called cadavre exquis (exquisite corpse), Apichatpong Weerasethakul — who is credited here as a mere “story editor” — and his crew meander from the northern provinces of Thailand to the south and, in a series of chance encounters, ask street vendors, farmers, local theater groups, and children to collectively tell a story. Each storyteller has to continue the tale where it had been left off. With each new encounter, the narrative evolves and changes, absorbing melodramatic and supernatural elements rooted in Thai soap operas and folklore, and extending the telling into the untold. Together, they slowly turn a fairly straightforward exposition into a polyphonic and heteroglossic tale of humans, animals, and aliens. The daisy-chain narrative of interlocking vignettes is shaped through speech or sign language, song and dance or radio broadcast, and grows more outlandish by the mile. Filmed on 16mm over the course of three years during Thailand’s economic crisis of the late 1990s, Mysterious Object at Noon already shows the rigorous attention paid to intricate sound recording and design, as well as uncanny narrative structures, that would characterize the director’s later film and video work, highlighting the full potential of cinema as a resonant form of composition and fabulation. “Less an anomaly than a secret skeleton key to Weerasethakul’s work… Mysterious Object at Noon revels in the myriad ways a story can be transmitted.” (Dennis Lim)

“You’re likely to be utterly enchanted by this unique dish of entertainment that may be the beginning of a new art form: Village Surrealism. Mr. Weerasethakul’s fifilm is like a piece of chamber music slowly, deftly expanding into a full symphonic movement; to watch it is to enter a fugue state that has the music and rhythms of another culture. It’s really a movie that requires listening, reminding us that the medium did become talking pictures at one point.” (Elvis Mitchell)