In the context of Courtisane Festival 2022 (Gent, 30 March – 3 April 2022). Curated by Stoffel Debuysere with Ricardo Matos Cabo.

Diz-se que na morte se vem sempre de longe

ao encontro de alguma coisa.

Reencarnamos no reconhecimento de uma voz,

e qualquer voz longínqua nos traz a certeza familiar

de não termos estado nunca sozinhos.

Porque nos reconhecemos nos bancos de jardim

onde nunca estivemos sentados.

Porque a lembrança que se extingue

é na memória que perdura.

Que mistério de memória é essa,

a da vida que, rasurando,

escreve de novo o que não deixa de sentir?

They say that in death one comes from afar

to encounter something.

We find reincarnation in the recognition of a voice,

and some far-off voice brings us that familiar certainty

that we have never been alone.

For we find familiarity on a park bench

where we have never been seated.

Because a recollection that fades

lives on in our memory.

What mystery of memory is this?

That of life, which rubs things out,

then rewrites what it continues to feel?

– Sérgio Godinho, original poem from Encontros

Encounters were at the heart of the life and work of Pierre-Marie Goulet (1950-2021). His filmmaking consisted of a process of searching and accumulating elements that then needed to be forgotten, to be reborn in ways that he himself could not have anticipated. What interested him the most were those small miracles that would emerge almost by chance. “I need to impregnate myself in an obsessive way with a universe that will then give me back the film,” he said. This process of finding and connecting unsuspected threads, geographical, cultural, or cinematographic, was nowhere as pronounced as in Encontros (2006), a film that revealed itself at the crosspoint of different paths and times based around the polyphonic songs from southern Portugal’s Alentejo region. The film grew out of the desire to extend the adventure of a previous film, Polifonias (1998), and to “circumscribe the presence of a sonorous, musical, poetic, human tribe, an analogical and surprising tribe whose territory does not correspond to any geographically known territory”, but it developed into a form entirely of its own, as a resonance chamber where a multiplicity of invocations resound.

Invocations such as that of young poet António Reis, not yet a filmmaker at the time, who became mesmerized by the songs of Peroguarda villagers and decided to visit the village in 1957, where he recorded poems recited by inhabitants, amongst whom the extraordinary Virgínia Maria Dias… Of Corsican ethnomusicologist Michel Giacometti who moved to Portugal two years later, where he would dedicate the rest of his life studying and recording popular oral traditions which were being lost or forgotten. It was Reis who sent Giacometti to Peroguarda where he would return periodically, and where, according to his wish, he was buried… Of poet Manuel Antonio Pina who, accompanied by other aspiring poets, chose to follow in the footsteps of António Reis in the mid 1960s… Of filmmaker Paulo Rocha, who shot his second film, Mudar de Vida (1966), in the village of Furadouro, setting the story among the fishermen who had fascinated him during his childhood. It was again Reis, having already worked alongside Rocha as assistant director of Manoel de Oliveira’s Acto da Primavera (1963), who wrote the film’s dialogues… From these intertwining invocations Pierre-Marie Goulet has crafted a tender meditation on the persistence of memory, sharing with us the echoes of a time that has passed, of a culture that is at risk of being erased. Not as a lament of what has been lost, but to make room for all that is alive.

Encontros acts as a guiding thread for this program, which brings together works by Pierre-Marie Goulet, Margarida Cordeiro and António Reis, Paulo Rocha, and Manoel de Oliveira; but also of Jean-Daniel Pollet, close friend and collaborator of Pierre-Marie Goulet, with whom he shared a profound love for the spaces, the rites, the memory and culture of the Mediterranean; as well as of Sumiko Haneda, who worked with Paulo Rocha on two of his films, and whose Ode to Mt. Hayachine (1982) provides another echo of traditions whose vital force continues to reverberate in the present.

——

In the presence of filmmaker and educator Teresa Garcia, who collaborated on the films of Pierre-Marie Goulet and with whom she developed Os Filhos de Lumière, a remarkable film education movement in Portugal.

Thanks to Teresa Garcia, Paulo Trancoso (Costa do Castelo), Martine Barbé (Image et Création), Sara Moreira (Cinemateca Portuguesa), Manuel-Casimiro de Oliveira, Sumiko Haneda, Tokue Sato (Kanatasha), Takeshi Yoshida (Japan Foundation), Christophe Piette (CINEMATEK), Matteo Boscarol, Rita Morais.

Encontros

Pierre-Marie Goulet, PT, 2006, HD, 105′

Portuguese spoken, English subtitles

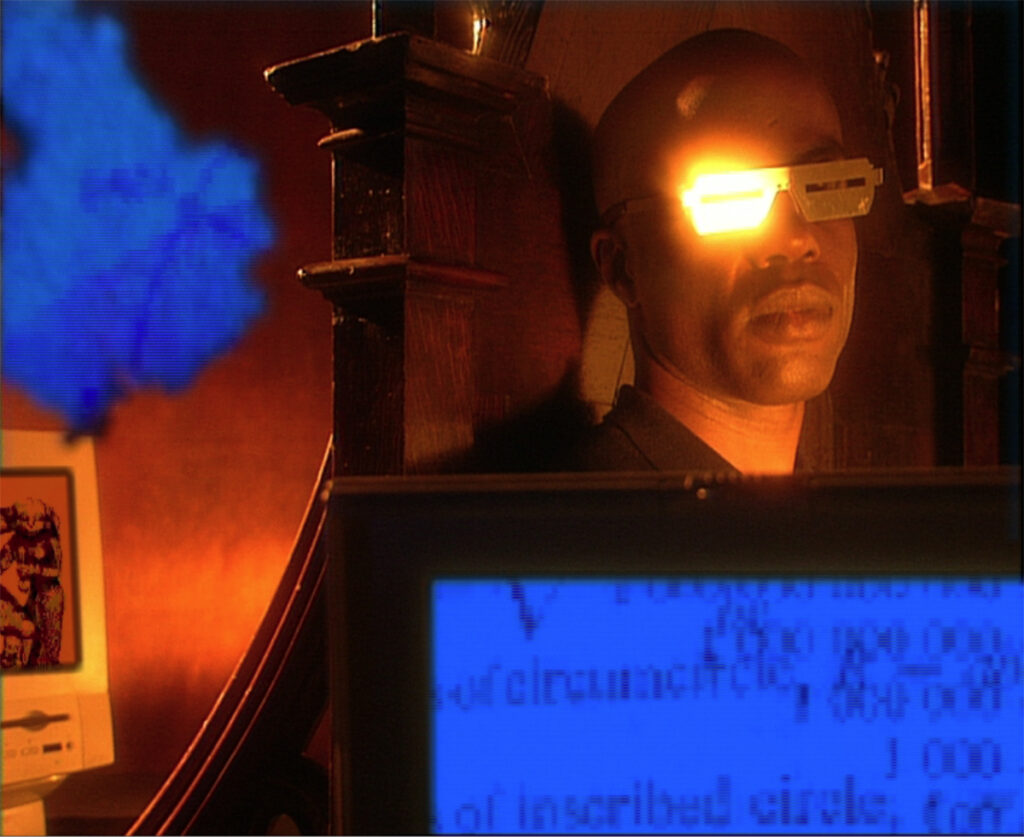

Mesmerized by the songs of Peroguarda villagers in southern Portugal’s Alentejo region, young Portuguese modern poet António Reis, Corsican researcher of Portuguese folk music Michel Giacometti, and film director Paulo Rocha visited the village one after another in the late 1950s. Encontros aims at circumscribing a tribe made of sounds, music, poetry and people; an analogical and outstanding tribe that doesn’t belong to any geographically known territory. The film intertwines different present and past gatherings between people and memories. Through that intertwining, one is made to wonder about what one is made of and how memory, the way others view us and the act of sharing enriches our lives.

“After finishing Polifonias, a film dedicated to Michel Giacometti, the desire was born not to lose everything that had been offered to me throughout the shooting and that I had not used in the final editing: songs, narratives, poems that were recorded and whose memory risked being lost if they were not integrated in a new project. There was also the desire to follow some of the paths that had been indicated to me during this time: that of the visit of António Reis, then still a poet, to the village of Peroguarda in Alentejo, the very same place in which Michel Giacometti wished to be buried, and others I wished to visit for my own reasons, such as, for example, to approach Paulo Rocha’s film Mudar de Vida, which fascinated me particularly by the interaction between the narrated story and the end of the fishing communities of Furadouro. Little by little it became clear what, beneath the surface, constituted in my mind one of the faces of Encontros: the echo of the past, of a time gone by, of a culture which had died out, but an echo one hears in the present and which resounds in its appeals. It thus became a question not of deploring what has disappeared, not of making a nostalgic return to the past, or bringing fragments of the past into the present, but of letting go of memory to make way for the living.” (Pierre-Marie Goulet)

Polifonias – Paci è Saluta, Michel Giacometti

Pierre-Marie Goulet, FR, PT, 1998, 35mm, 82′

Portuguese spoken, English subtitles

35mm print courtesy of Cinemateca Portuguesa

Michel Giacometti, “The Corsican who loved Portugal” was born in Ajaccio. In 1959, he arrived in Portugal and never left. For thirty years, he collected music, tales, stories and poetry, sayings and adages, recipes for popular medicine, giving back to men and women the pride of their culture. This Corsican reinvented himself an island in Portugal, saving the roots of others to discover his own. By saving the memory of a people, he pursued a quest, that of the sometimes-mythical roots that we all carry deep within ourselves. It is on this terrain that Polifonias crosses the traces of his journey, questions the living memory of the elders, and shows the ever-present vivacity of traditional music in Portugal and Corsica.

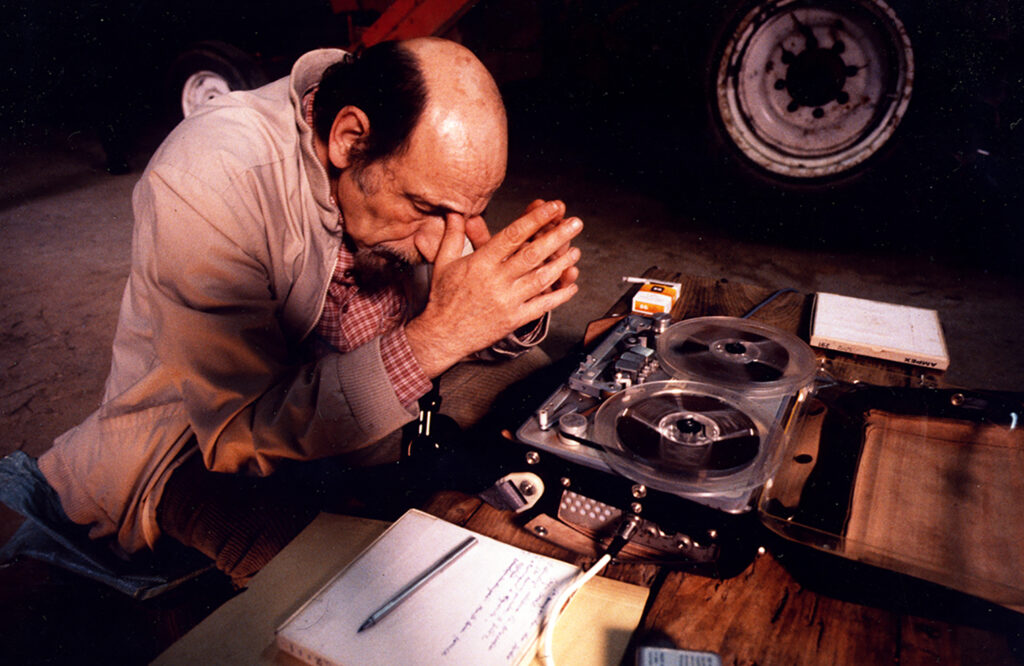

“I made the Giacometti film with Antoine Bonfanti, a sound engineer who had always worked with me since 1978. He was the great engineer of direct sound. Chris Marker, Godard, Marguerite Duras, André Delvaux, Resnais… Bonfanti, who was a Corsican, before arriving in Portugal heard about Giacometti, who was also a Corsican. They struck up a friendship and thanks to that we developed, the three of us, a project that was to be filmed. But Giacometti died before we could start the film. Five years later Antoine and I still wanted to make the film and we finally decided to make Polifonias, which took up Giacometti’s desire to bring together the Corsican and Alentejan cultures. I added to the film a tribute to Michel Giacometti’s own path.” (Pierre-Marie Goulet)

Acto da Primavera (Rite of Spring)

Manoel de Oliveira, PT, 1963, 35mm, 94′

Portuguese spoken, English subtitles

Restored 35mm print courtesy of Cinemateca Portuguesa

While location shooting for another film, Oliveira stumbled upon the subject for Rite of Spring, the annual passion play enacted in a village in the same remote northern region of Portugal (Trás-os-Montes) that would inspire Antonio Reis’s most important work. Intrigued by the ritualistic and incantatory qualities of the vernacular production, Oliveira returned with Reis and set about directing the villagers in a re-enactment of the passion play, adding a rich performative layer to the film. A fascinating meta-ethnographic study of local tradition and history that folds in on itself, Rite of Spring climaxes unexpectedly in a furious Bruce Conner style apocalyptic montage that links Christ’s death to the violent lunacy of the Vietnam era. (Harvard Film Archive)

“There was stubbornness in his consciousness, that of a solitary man who, through his camera, reacted to what he saw by trying to perceive where the good was and where the evil was, what were the forces of things which he saw. You could clearly feel the hesitation. And in the midst of the struggle, of the hesitation, suddenly, a decision: this angle, that frame. And such a formal decision did not come from any model, it was like a visceral, instantaneous reaction, without a parachute, taking the risk… What struck me most was this intimate exercise in the rough and tumble of perceiving the world, the camera’s gaze, if you like, but how the perceived matter resists our will, which is good. The camera shakes because it cannot properly perceive what it is seeing. He has never been greater than in these moments, and never has he been more inimitable. This side of him is like an X-ray of emotion, of conscience, of doubt, and there are few equivalents in world cinema.” (Paulo Rocha)

Mudar de Vida (Change of Life)

Paulo Rocha, PT, 1966, DCP, 94′

Portuguese spoken, English subtitles

Restored version courtesy of Cinemateca Portuguesa

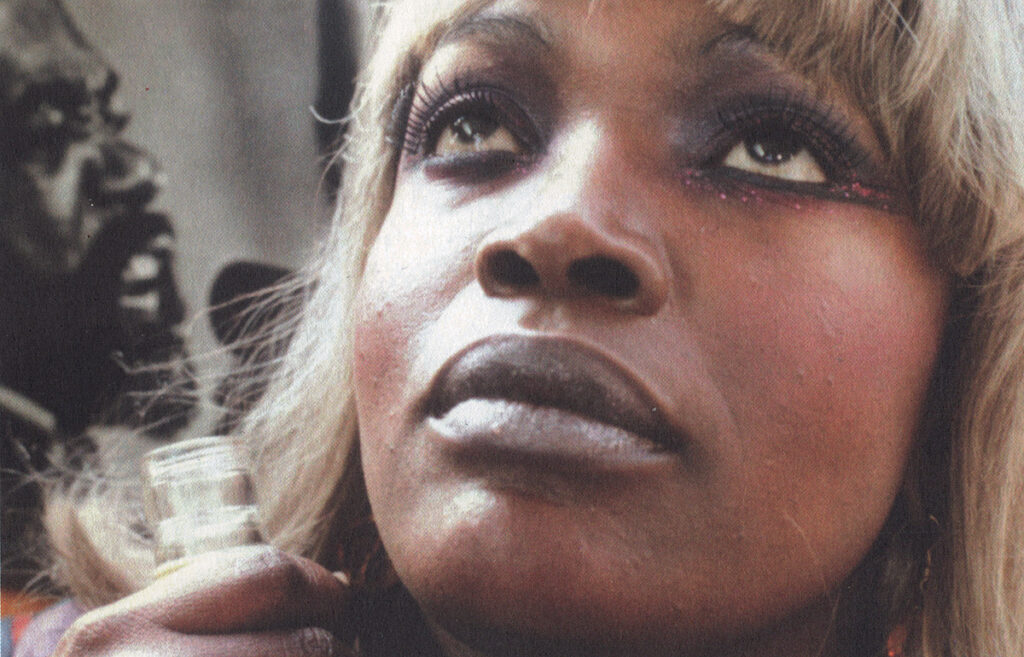

The second and arguably most important film by Paulo Rocha, one of the central figures of the Novo Cinema, Mudar de Vida is a direct response to Oliveira’s Rite of Spring and an important precursor to the radical documentary shaped fiction of António Reis and Margarida Cordeiro. Captivated by the remote Portuguese fishing village of Furadouro, Rocha chose not to make a traditional documentary but rather to engage the specificities of the people and place through fiction, crafting a melancholy story about a soldier’s return to a changing world. Inspired by his experience working with Oliveira on Rite of Spring, Rocha “cast” the local villagers as themselves, interspersed with experienced actors led by the great Isabel Ruth, who would go on to become an Oliveira regular. The poetry of the local vernacular is captured in the textured dialogue written by António Reis, who met Rocha through Oliveira. Despite the steadily building critical acclaim that followed the release of Mudar de Vida — and despite its controversial depiction of a disillusioned Angola War veteran — Rocha effectively ceased filmmaking until the 1980s. (Harvard Film Archive)

“António gave me a great lesson. He worked on the dialogues for six months, scratching and throwing them away. Every day thinner, always in a cold sweat, searching for the comma, the pause, the secret and expressive assonance. The dialogues, dragged out in irons, arrived at the filming at the last minute, and there was no time to reflect on them. It was only years later, when Mudar de Vida had its premiere in Tokyo, that I had the opportunity to study them. The work of translating them into Japanese was very slow, and only then could I discover the musical concision, the secret wealth of those phrases written with an infallible ear. How many dialogues in our language can compare to that?” (Paulo Rocha)

Trás-os-Montes

António Reis, Margarida Cordeiro, PT, 1976, DCP, 111′

Portuguese spoken, English subtitles

New digitized version courtesy of Cinemateca Portuguesa

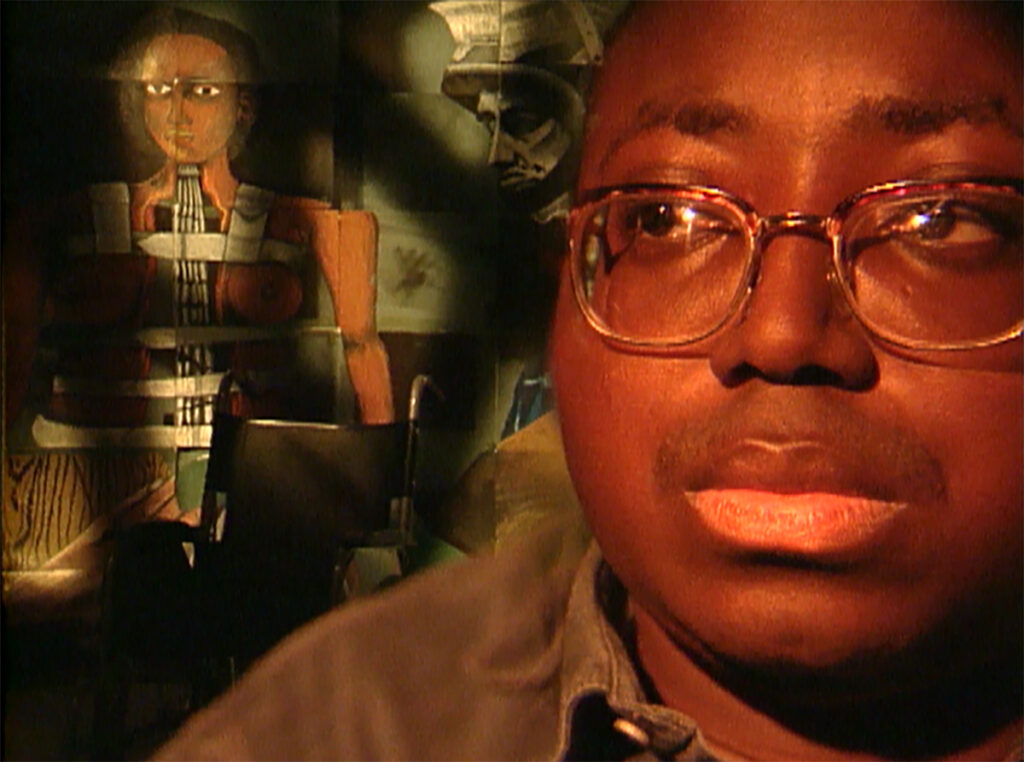

For Jean Rouch, “this film reveals a new cinematographic language.” Reis and Cordeiro’s indisputable masterpiece exploded the meaning and possibilities of ethnographic cinema with its lyrical exploration of the still resonant myths and legends embodied in the people and landscapes of Portugal’s remote Trás-Os-Montes region. Evoking a kind of geologically Bergsonian time, with past and present layered upon one another, Trás-os-Montes interweaves evocative recreations of the ancient worlds and encounters with atavistic peasantry, following the pilgrim’s path traced by Reis and Cordeiro as they led their skeletal crew from village to village in search of the poetic essence of the Portuguese language and imagination. Painstakingly researched and shot over the course of one year, Reis and Cordeiro became intimate with every person included in their ambitious film, carefully selecting the different voices, faces, and gestures that would together provide an extraordinary composite, associative, and mythological response to the question of how to define a ‘national cinema’. (Harvard Film Archive)

“António Reis was a kind of visionary scientist. He looked at the world, at the stones, at nature, with the eyes of a sage and a poet. He found in them the magical side and the geological side… António and Margarida’s film was a masterpiece that brought them European fame. When the film premiered in Paris, Le Monde published a terrorist order signed by Joris Ivens and Jean Rouch, the two supreme masters of documentary cinema: ‘Allez voir, toutes affaires cessantes, Trás-os-Montes!’” (Paulo Rocha)

Hayachine no fu (Ode to Mt. Hayachine)

Sumiko Haneda, JP, 1982, 16mm, 186′

Japanese spoken, English subtitles

Print courtesy of Japan Foundation and Kanatasha

Shot in the foothills of Iwate Prefecture’s mystical Mt. Hayachine, the film records a year in the life of the area’s villages and villagers as they prepare for kagura performances, a dance-theater form with origins in religious rituals (now mainly performed for tourists). The film can be enjoyed and processed on many levels: a musicologist’s fascinating glimpse into kagura traditions and performances; an ethnographic portrait of rural life and village hierarchies; and most of all, a study of a key moment in Japanese society, when, even as Haneda filmed, rural lifestyles were exposed to modernity: paved roads, cars, and tv sets. Fittingly, the film’s true beauty comes not through its thesis, but in its attunement to the mountain’s own intricate rhythms. (Pacific Film Archive)

Sumiko Haneda is one of the most prominent documentary filmmakers from Japan and one of the few women working in non-fiction cinema there in the postwar period. Born in 1926, in Dalian, China (then Manchuria), in 1949 Haneda entered Iwanami Shoten, a publishing company producing educational and promotional films, where she would make films about the arts, education, and nature. In 1976 she directed her first independent film, Usuzumi no sakura (The Cherry Tree with Gray Blossoms, shown at the Courtisane festival 2021). She continued to direct over 80 short and long films and worked with Paulo Rocha on A Ilha dos Amores (1982).

“What is art for, what is fiction for, what position does the profilmic material occupy in a movie, what position does fiction occupy in art? What about the artist? What happens to the artists filmed? Rarely in the history of cinema have such essential questions been asked in such a direct, simple, generous, and intelligent way. I am a filmmaker, and until now I believed that I would be closer to the truth if I approached it through fiction, but now, after seeing Haneda’s Ode to Mt. Hayachine, I realize that the idea is an arrogant one, we must take advantage of this opportunity, we must learn to see reality correctly to know the truth. Ode to Mt. Hayachine gave us the best example of this.” (Paulo Rocha)

Trois jours en Grèce (Three days in Greece)

Jean-Daniel Pollet, FR, 1991, DCP, 94′

Greek / French spoken, English subtitles

Restored version courtesy of La Traverse / English subtitles created by Courtisane

Jean-Daniel Pollet used to say that Greece was his “second home”. He encountered it in 1962, at the age of twenty-six, during the journey that preceded the making of Méditerranée (1963). On his return, he spent several months locked up in a cellar looking for the montage, which he found one Easter day. Never before had we seen such a thing: a series of images that return and are arranged in a fugue whose loops replay the circularity of the journey around the Middle Sea. Over the years, Pollet never stopped going back to Greece, filming some of his major films there. In 1991, Three days in Greece closed the series. The filming, three decades after the first trip, would be his last stay in the motherland. The last Greek film, it is also, in accordance with the deep law of Pollet’s cinema, a return to the origin, remake, reworking and relaunching of Méditerranée. Reinvention of its broken circularity, of its syncopated pace, the same vertigo danced above the abyss, but untied, unfolded, lightened or lifted by the grace of a new serenity… Pollet’s cinema, transported by the spirit of dance, reaches in Trois jours en Grèce the amplitude of a cosmogony. (Cyril Neyrat)

“In a classic film, Belmondo gets out of a car, enters a restaurant, goes to the phone. We follow him. It’s not editing, even if there are connections, several shots: we just follow him, from one shot to the next. The ellipsis — you cut a little bit of time and the viewer is supposed to understand what you cut — it’s still not really editing, you have to cut even more — you don’t know why you go from one shot to another. Then you get a certain logic, poetry… For me, this language comes naturally: there, long live the editing and the mechanism of dreams soaked in the unconscious!… long live the editing at night just before going to sleep. An enlightening montage, as with dreams, where there is no other logic than that of the unconscious. A logic which is that of happiness or that of suffering.” (Jean-Daniel Pollet)