by Serge Daney and Jean-Pierre Oudart

Originally published in ‘Cahiers du Cinéma’, no. 276, May 1977. Translated by Kelsey Brain, Ted Fendt, Bill Krohn. ‘Trás-os-Montes’ will be shown during the Courtisane Festival (17-21 April 2013), as part of the programme “Once Was Fire”.

Cahiers: What can you tell us about the shooting, about the conditions in which you worked with the peasants of Trás-os-Montes?

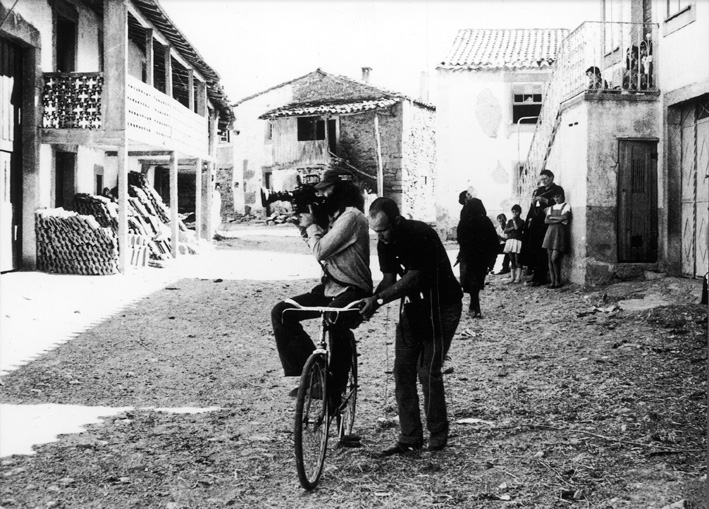

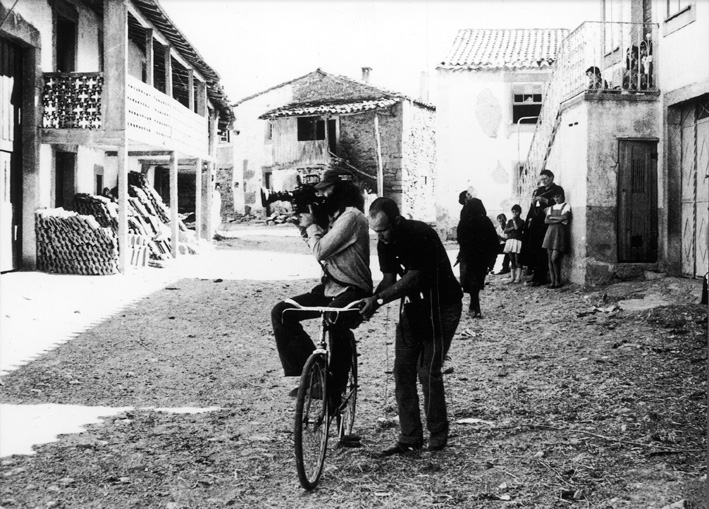

A. Reis: I can tell you that we never shot with a peasant, a child or an old person, without having first become his pal or his friend. This seemed to us an essential point, in order to be able to work and so that there weren’t problems with the machines. When we began shooting with them, the camera was already a kind of little pet, like a toy or a cooking utensil, that didn’t scare them. So using their lights in their homes or setting up reflectors in the fields to have indirect light wasn’t a problem. It was a sort of game at the same time. So it was possible to insist on certain things, most often with tenderness. And if we were having a problem, they understood very well. A very important thing: they were able to confirm from our work that we were also “peasants of the cinema,” because it sometimes happened that we were working sixteen, eighteen hours a day, and I think that they liked seeing us working. And when we needed them to continue working with us, even while leaving the animals without food or the children without care, they didn’t feel, I think, it was a constraint. It was admirable to see this.

You know, I don’t have a tautological conception of people, but I believe that in the Northeast, they have a very special way of treating people. If you arrive – suddenly – they greet you, they open their door to you, they give you bread, wine, whatever they have. At the same time, they are not “kindness personified” because they are also very hard. Only they go abruptly from gentleness to violence.

Cahiers: What relationship did they have with cinema, or television?

A. Reis: In the village where we shot, I can tell you that there was neither cinema nor television. (He makes a drawing on the paper tablecloth.) Portugal is like this, Spain is like this, the Northeast is here. Here, there is a town named Bragança and, there, another named Miranda do Douro. All the villages we shot in are situated near the border and in the vicinity of these two towns. So the peasants know that there’s cinema and television in Brangança, but that’s all. In many of the villages, there is still no electricity. The connection to cinema is still a connection to photographs, quite simply.

Cahiers: How, as soon as you had had the idea and the project of the film, had you thought to avoid looking at these peasants through an ethnographic lens?

A. Reis: You know, I believe that the ethnographic way of seeing is a vice. Because ethnography is a science that comes afterwards. Similarly, we did not see the people of the Northeast from a picturesque or a religious point of view. We were obviously very interested in the

anthropological problems posed by the region, in Celtic literature, etc. We read all of your Markale (the French writer -Ed.), because the Celts are still there. We studied Iberian architecture because the architecture of the homes there was not born by spontaneous generation. But it was always with the aim of choosing, of intensifying. Because if we read a landscape solely from the point of view of “beauty,” that’s not very much. But if you can read at once the beauty of the landscape, the economic aspect of the landscape, the geographical-political aspect of the landscape, all that is the reality of the landscape. The integrated land, without any transformation, the cultivated land, etc. So, on the subject of the Northeast, we treated dialectically everything we knew, everything we learned from the people, everything we discovered ourselves. Because it was also possible to discover things. Margarida was born in the most violent part of the Northeast. Even today, she remembers the taste of the wine, the childhood legends and the nightmares. All this became material, with a certain depth.

Cahiers: But for someone who lives in Lisbon, what is the Northeast?

A. Reis: It’s very far. It’s from there that electricity, almonds, good sausages, hams, iron, etc, comes. What the peasants of the Northeast say about the capital is what is said about the Northeast in Lisbon , except for emigrants from the Northeast in Lisbon. To them, even if they’ve lived for twenty or thirty years in Lisbon, if you say the name of a tree in their subdialect, they still tremble.

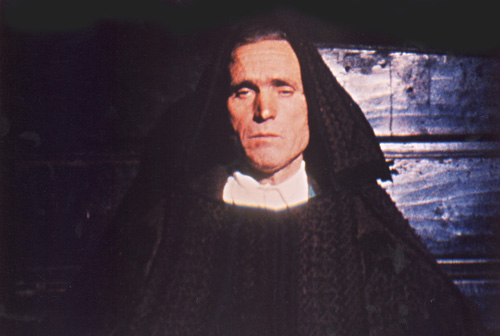

Cahiers: Something that’s striking in the film is the absence of the Catholic Church, of religion. Because according to what we know in France about Portugal after April 25th, and particularly about the North, it seems to us that the Church played an important role…

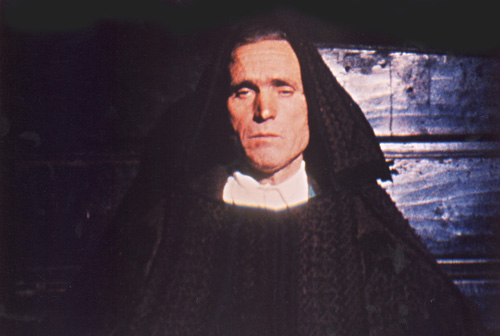

A. Reis: I can tell you that on this subject, we adopted, Margarida and I, a principle of tabula rasa. In the film, we never deal with institutions. Because Catholicism is a very recent religion there. You sense in the film that there are much older religions and among the people themselves, Christianity is a very superficial thing. It’s not an exaggeration or a poetic liberty to say that they are druids. If you hear them talk about trees, about how they love them…there is there something very old that has nothing to do with Christianity, which had to be made present through its absence. The film is a fresco, an epic of the Northeast, it’s vaster than a small chapel in an artificial world, with the village priest, etc. I think that a film with all that as a subject should to be made differently than the one we made, with other implications.

Cahiers: But you can’t deny the Church’s influence recently in the North of Portugal. What did it use among the peasants in order to make them move politically?

A. Reis: You know as well as I the priest’s game with the peasants. He manipulates them with death, the afterlife, he scares them. He uses the fact that the people, for the time being, need certain fetishes, so it’s easy to impress them. But does this mean that deep down the people are what they say to the priest, what they do with him? No. All that we feel, when we’re in contact with the peasants, about their revolt, about their philosophy, about their daily life, is that there are very different religions, more ancient…

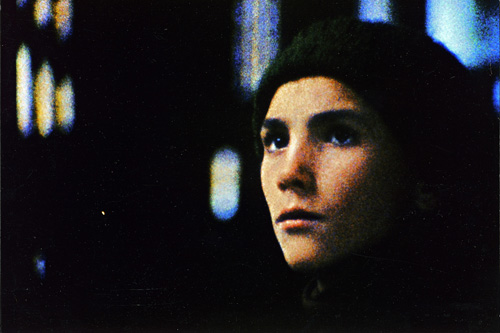

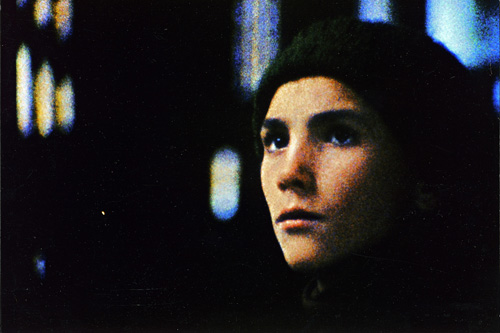

Cahiers: That would be in keeping with the feeling at very the beginning of the film where we see a child, a shepherd, who sees an inscription on a rock, an inscription that refers to a very distant past.

A. Reis: You know, there are three shepherds in the film. All three are different. The first, the one you’re talking about, is a force of nature. He is like a Fulani in Africa or a shepherd in the Middle East, a shepherd who has a profession, a code with his sheep, who walks in the night, who still belongs a bit to the Neolithic age. What he says to his sheep is a code where it is difficult to separate the music, the phonetic and lexical aspects: you feel a shock between these elements. And he speaks a subdialect older than Portuguese. He is very different from the last shepherd. He’s a primitive in the good sense of the term.

Cahiers: How did the idea of the film come to you?

A. Reis: I’ve already said that Margarida was born there. As for me, I was born in an already eroded province lacking force, lacking beauty, lacking expression, 6 km from Porto. So inside me I had the desire to be reborn somewhere else. And the first time that I went to Tràs-os- Montes with an architect friend, I felt that I was born there. So, I’d known the province for several years and, in working with Margarida, in going there often, I said to myself that it would be nice to make a film there because everything came together in a cinematographic sense. To the point that when we began shooting, a lot of location scouting had been done long before. That doesn’t mean that we didn’t plan things, but it was a flexible plan. In many scenes, for example, it is very difficult to distinguish what was filmed en direct from what was not. The dialectic of these two aesthetic positions was hellish for us. But we believe we’ve succeeded in making, not a synthesis, but a confrontation of contraries. Even en direct, on the one hand, we needed all the speed and all the surprise but, at the same time, we cleaned up some parasitic things that didn’t make sense or that were gratuitously populist. And for that, we needed an insect’s eye.

Cahiers: I had the feeling that, during the whole first part (the one with the children), you were using the fiction to progressively bring out more naked information, more closely related to what one expects from a documentary.

A. Reis: But when the mother is telling the story of Blanchefleur, is it fiction or documentary? It’s both. In a village it can happen that an event is fiction. So what is surprising about a village is that if you are there, you see only the golden dust, animals at the spring, etc. But if we can go from one house to another, then to a river, then through a door, things become so complex that you can no longer talk simply about fiction and documentary.

In this house, you can hear, precisely, that mother telling the story of Blanchefleur orally, while working. And the children of the middle ages are like Blanchefleur in images. What you understand with these Portuguese villages is that it’s a vice to separate ancient culture, the

civilizations that came after, and everyday life today. It is there precisely, in this refusal to separate, that I find a progressive and revolutionary element. Because I think that the masses there know how to assimilate from a critical point of view of the forms of life that owe nothing to the city. Because these people aren’t inclined to always lose. They begin to realize, seeing their sons returning from Europe, that that doesn’t make up for anything. The sons who return from Europe build a house “next to” the others, fence it in, and the parents think, “My son has gone mad!” And so it arises that the old disagree with their own children. They know very well that they have a richness and that there is a genocide against them. This is why, at those times, they can say, “We’re going to cut off all the supplies, the food for Lisbon.” It’s not only to be reactionary; it’s that they want their hands and their heads to still have value.

Going back to what you said: in fact, there is a turning point in the film. This turning point is the lyrical quality that is always threatened. Even when the children amuse themselves at the river, they discover death with the frozen trout. The big dusty house or the deaths or the child who plays with the top (who is the one who goes to the mine), it is always a threatened world. I believe that the film is always transforming. The so-called “finale” has to act like a boomerang: viewers need to be compensated by the lyrical space and time of the first part in order to support what follows. When the blacksmith regrets that people are leaving the village, this refers precisely to the mutilated children and the deaths from the colonial wars, these are them. Those who are going to come to Lisbon, to Europe, in the slums, in the factories, etc. That’s why we treated these young children with so much intensity. If you go there, you’ll see, they’re like that, there’s no naturalism, they’re still sort of angels.

Cahiers: There’s also the feeling that it’s them who are the link with the past. The adults are kind of in the background. They appear through the voice over, not onscreen.

A. Reis: Because there are no adults there. The voice over you hear, a little violent, a little oppressed, is the voice of a character who we see for a brief moment in the film. It’s a miner’s son, an executive. His father spent fifty years at the mine. The voice of this man is traumatized. He speaks of the old community of miners who were former peasants. Never in our film do we talk about the communities of villages, but you have to feel that they exist. We do the dance, we walk in the dark communally. The voice over counterpoints the life of the miners like the train whistle counterpoints Pergolesi’s music that we hear for a moment. There is always a crossing, a dialectic of the sound with the image that interests me a lot more than all these stories of connections, of ellipses and other rules from film manuals.

Cahiers: At one point in the film you quote a text by Kafka which says that people are far from the Capital, therefore from the Law, which they try to guess but which they never manage to do because the Law is possessed by a small number of people, etc. Can we consider that this is shorthand for the historical situation of Tràs-os-Montes in relation to Lisbon?

A. Reis: Yes. We translated the text by Kafka into the subdialect and, as a result, this text became very guttural, very expressive, endowed with an extraordinary force. They have a marvelous word designating the manner in which the nobles use the Law to their benefit: “baratím.” Because the laws of the community are flexible, they are transformed by historical change. These are of course oral laws, they aren’t made once and for all, they are flexible. And it is precisely because of this flexibility that they were liquidated by the written Laws. One day, it is such and such a shepherd who leads all the sheep to graze, another day it’s another shepherd. There’s a sort of primitive communism in this region. And we feel that at times they are closer to the future than people in the city. For example. if Lisbon lacks water for twenty-four hours, there is a collective neurosis! How, given the toughness of his life, does a peasant face snow, fire, heat, etc. With what endurance. Even when certain peasants were imprisoned by the PIDE [1], they succeeded at resisting. Why? And how many friends have I known in Porto who spoke a lot and very loftily and who, when they were imprisoned… I don’t want to say that the peasants are more courageous and the other more cowardly. But why, for example, when the peasants of Baixo Alentejo were arrested, did they have an endurance that people from the cities did not have?

Cahiers: We get the feeling that your film is made of image-sound units against which you refuse all cheating…

A. Reis: We have made the sound synchronous, obviously. We have, like you say, organized the units, as if it were possible to have a symphonic sound. These are units which will sometimes echo further on. I’ll give you an example: when the old woman in black has just told the child who has fallen, “Do not cry I’m going to sing ‘Galandun’ (a song from the Medieval Ages) to you,” there is a voice that says, “the dancers who rise up, who rise up…” And she is already working to memorize what she has lost and we see then the men who dance close up, blurred, and then from far away, like on a postcard. We allow the spectator the attention to think: “Look, a postcard!” Because the peasants never actually danced at that place. It’s what we ourselves imagine today. But pay attention: you have to to wait until the end of the film to really give that shot meaning. Because later, we see the old woman who watches and you might believe that she watches the dancers, but that’s not true. These are successive disillusions, but not traps. Often people say of the film: the rhythm is too slow. This is because you have to wait until the end of the film to say certain things. And how the different units proceed dialectically, for us, is very important. What’s bothered us a lot is that we edited in black and white and we haven’t had enough time afterwards to work on the color. Working twelve months at an editing bench assembling in black and white a film that we should have seen in color!

Cahiers: Who has the film been shown to? What reactions has it provoked?

A. Reis: First we showed previewed the film to the peasants who we shot with. In general, they liked the film, they reacted very well, including to the “connotations.” We’ve had some negative criticisms but they were from reactionaries like the kind you find in Lisbon or Porto. They reproached the absence of the Christian religion, of not having shown dams, the traditional cuisine, the poverty, etc. They even wanted to burn the film and to destroy the negatives. But that’s a very limited reaction, coming from people I know and who spend their lives in cafes. The important thing, for us, was the peasants…

Cahiers: But exactly how can a film contribute to helping these peasants who are otherwise so cut off from film?

A. Reis: Of course, there are cinematic language problems. They don’t possess this language there. But there are elements which are very important in their everyday lives, things which relate to the theater of the middle ages. They live in a space, at home or in nature, that is already cinematic. I’m certain that if they study film, they will become filmmakers. A peasant said to me one day, “What? You’re leaving for Lisbon without ever having seen the light which goes from such-and-such kilometer to such-and-such kilometer? How can you?” With difficulty I find people in Lisbon who talk to me about the light on the bricks or on the streets. So when the peasants saw the film, they recognized these things they liked and that belonged to them, even if sometimes our imagination or our freedom of expression bewildered them. For example, the snow scene. They’ve never eaten snow like you see in the film but they’re affected by snow, by the beauty of snow, by the glare of snow. So, as there are people who eat dirt or straw, I made them eat snow.

Cahiers: I would like to ask you a more general question about the cinema of Portugal. First, does a “Portuguese cinema” exist? Then, what has changed since April 25th? And you, what do you think is working and not working?

A. Reis: My position on this subject is somewhat like that of Seixas Santos. We think that there’s no “Portuguese cinema.” We ourselves manage, whether during fascism or after April 25th, in a situation which is characterized by a lack of connections with world cinema, a lack of control over our means of production, a lack of real and sufficient experience. There are isolated cases, like the case of Portugal since the 19th century. We have some quality but we don’t have quantities of quality. In that sense, you can’t talk about a Portuguese cinema. Even the generation of 1962, whose efforts were very important, knows very well that these efforts have been very individual. Sometimes they unite in order to defend themselves, in the name of a certain political engagement and not in the name of romanticism. I don’t believe that things have changed much since April 25th. These are cooperatives and independent filmmakers, but it’s still with money from the state. We make films which are neither seen, nor sold and we don’t have any more money to make others. It is regrettable that we work like this, always wondering: “are we going to be able to make another film?”

Cahiers: What kind of reactions did your film provoke amongst filmmakers?

A. Reis: On this subject we rather like enfants terribles. Margarida and myself. We don’t recognize any influences. Even when people want to compare us to Manuel de Oliveira, we refuse it, even if we have great respect for him. Even if it’s only for the way he works, for his standards. Otherwise, the films that we want to make are perpendicular to those of Manuel de Oliveira. Because there is a tendency leaning towards the metaphysical in his films, remnants of Jesuitism, which don’t interest us.

Cahiers: What is striking is that Manuel de Oliveira and you, you have a point in common, you are both from the North, from Porto. And not from Lisbon. Is there not, in the cinema as well, a sort of overdevelopment of Lisbon which doesn’t produce great things…

A. Reis: I believe so. I think that the life in Lisbon doesn’t leave filmmakers a lot of time to go deeper into what they say. I don’t want to be hard on them because they’re my friends, but I believe that sometimes their way of life blocks them. I think they’re adult enough to know the fundamental reasons for why we are engaged in cinema. I believe that cinema is a matter of life and death. For us, we can’t cheat.

[1] Polícia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado (International and State Defence Police)