25 March 2013 20:30 OFFoff Cinema, Gent

What are we seeing when watching images flickering on the screen? One could say that the cinematic experience always involves an unique play of imaginary presence (perceptual experiences, fantasies, illusions) and real absence (what is represented but not really there). The act of perception may be real, but the perceived is merely a shade, a phantom, “a hallucination that is also a fact”. It is this fundamental tension between presence and absence, actual and perceptual, the visible and the spectre of the hidden, that is at the heart of Mary Helena Clark’s work. Taking cues from the fantasy and illusion of early cinema as well as the material and formal exercises of the avant-garde, her hypnotic pieces explore cinema’s primitive magic, hurtling us down the secretive rabbit holes of the moving image. After having screened several of Mary Helena’s films in previous years, Courtisane will once again showcase her work during the coming Courtisane festival (17-21 April 2013), with the screening of her latest short film, Orpheus (outtakes). As a prologue to this year’s festival, Courtisane will present at OFFoff six films by Mary Helena Clark together with a selection of works by other filmmakers that have inspired her practice.

“Here is a selection of my films from 2008 to 2012 with work by Hans Richter, Anne McGuire, John Smith, Ernie Gehr, Anne Robertson and Saul Levine.

Hans Richter’s Rhythmus 21 begins the program with an exploration of constructed space. It’s a minimalist play of dimensionality, finishing with a reinstatement of the flatness of the screen space. Anne McGuire’s I Am Crazy and You’re Not Wrong still startles me with the spontaneity of her performance. You can almost hear the twists of her mind and feel the tension of the single performer on stage, threatening to turn tragic. And like McGuire, John Smith’s a major and recurring influence. Leading Light, an early work, straddles lyrical and structural modes of filmmaking, using the basic tools of exposure and sound perspective to playfully undermine the veracity of film. Also, I am partial to movies made in bedrooms. Ernie Gehr’s Untitled (1977) was described to me by Ken Eisenstein years before I ever saw it. So for me, there’s a stacking up of the told-film, the film itself, and then how that film lingers in the mind, like a play of tenses. The shifts in Gehr’s film are magical whether imagined, experienced, or remembered. Going To Work by Anne Robertson is one of her quieter pieces. This diary film observes the world with a disconnect that rings true, with a mundane profundity that can hold the viewer in bewildering stillness. Saul Levine’s Dream Story gives me goosebumps. It’s directness reminds me of why I want to make films. The title of this program is taken from a Nabokov novel of the same name. He writes, “When we concentrate on a material object, whatever its situation, the very act of attention may lead to our involuntarily sinking into the history of that object…Transparent things, through which the past shines!” ”

Hans Richter

Rhythmus 21

Germany, 1921, 16mm, b&w, silent, 3’30

“I conceive of film as a modern art form particularly interesting to the sense of sight. Painting has its own peculiar problems and specific sensations, and so has film. But there are also problems in which the dividing line is obliterated, or where the two infringe upon each other. More especially, cinema can fulfill certain promises made by the ancient arts, in the realization of which painting and film become close neighbors and work together.”

Mary Helena Clark

By foot-candle light

USA, 2011, digital video, color, sound, 9’

“A walk through the proscenium wings. You close your eyes and suddenly it is dark.”

Anne McGuire

I Am Crazy and You’re Not Wrong

USA, 1997, video, b&w, sound, 11’

A wonderful witty work about nostalgia and desperation. Ann McGuire portrays a Kennedy-era singer performing in a space where theatre meets television. McGuire’s Garlandesque gestures provide both a sense of tragedy and humour. I am Crazy and You’re Not Wrong weaves narrative, performance, memory and history into a ironic and haunting work of unique proportions.

John Smith

Leading Light

GB, 1975, 16mm, color, sound, 11’

“Leading Light uses the camera-eye to reveal the irregular beauty of a familiar space. When we inhabit a room we are only unevenly aware of the space held in it and the possible forms of vision which reside there. The camera-eye documents and returns our apprehension. Vertov imagined a ‘single room’ made up of a montage of many different rooms. Smith reverses this aspect of ‘creative geography’ by showing how many rooms the camera can create from just one.” (A.L. Rees)

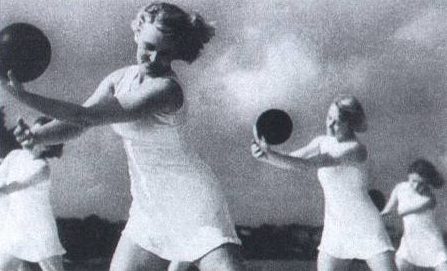

Mary Helena Clark

And The Sun Flowers

USA, 2008, digital video, color, sound, 5’

“Based on the true story of the wallpaper in my bedroom.”

Mary Helena Clark

After Writing

USA, 2008, 16mm, color, optical sound, 4’

“Scraps of text gathered from molding filmstrips and peeling chalkboards are photographed and intercut with pinhole shots from a schoolhouse. “

Ernie Gehr

Untitled

USA, 1977, 16mm, color, silent, 5’

“… a delicious slow pulling of focus over four minutes in which snowflakes, streaming like intercepted chalk marks, fall in front of what seems to be a field, then a pond, and finally is recognized as a brick wall.” (P. Adams Sitney)

Mary Helena Clark

Orpheus (outtakes)

USA, 2012, 16mm, b&w, optical sound, 6’

“An impossible film project: Buster Keaton stars in the outtakes from Jean Cocteau’s Orpheus, made by me for the cutting room floor.”

Anne Charlotte Robertson

Going To Work

USA, 1981, Super8 to video, color, sound, 7’

“Anne took the written diary form and extended it to include documentary, experimental and animated filmmaking techniques. She did not shy away from exposing any parts of her physical situation or emotional life. She became a pioneer of personal documentary and bravely shared experiences and observations on being a vegetarian, her cats, organic gardening, food, and her struggles with weight, her smoking and alcohol addictions, and depression (she was diagnosed with bipolar disorder). Romance (or lack thereof) and obsession are long-running themes in her films, as is the cycle of life.” (Harvard Film Archive)

Mary Helena Clark

The Plant

USA, 2012, digital video, color, sound, 8’

“A film filled with clues and stray transmissions built on the bad geometry of point-of-view shots.”

Mary Helena Clark

Sound Over Water

USA, 2009, 16mm, color, optical sound, 5’

“Blue water and blue sky meet on emulsion.”

Saul Levine

Dream Story

USA, 2001, digital video, color, sound, 5’

“Dream Story is about a dream I had of Marjorie Keller.”