28 March 2013 20:30 Galeries, Brussels

in conversation with Stoffel Debuysere

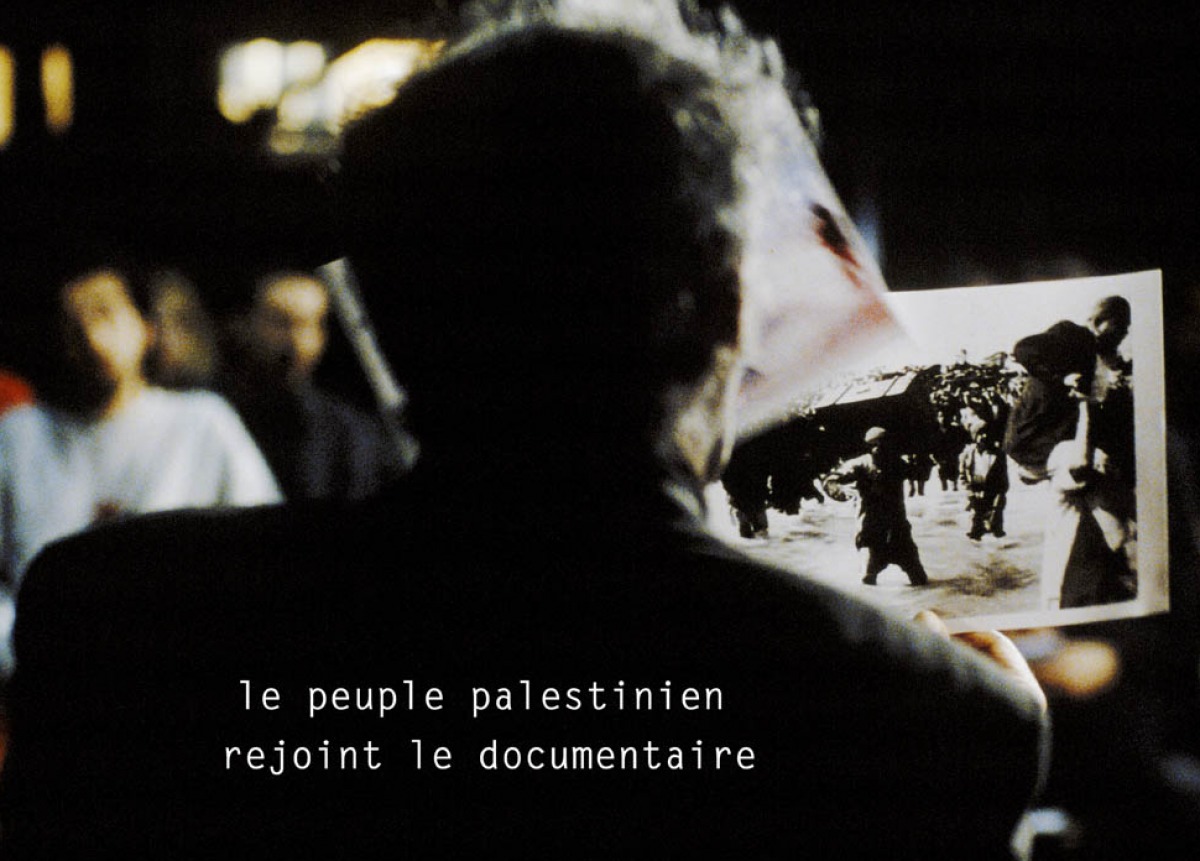

“As once stated in a Brecht play: if two things come together, you need a third thing. The third thing, back then, was political film making”. For about ten years, the film work of Hartmut Bitomsky could hardly be dissociated from that of Harun Farocki. In the second half of the 1960’s they both formed the backbone of the Projektgruppe Schülerfilm, an initiative of Berlin students building on the leftist intellectual legacy by combining militant cinema and Brechtian didacticism. After their studies, they continued to make a number of films together, and consequently co-founded the Filmkritik magazine as an outlet for their cinephile enthusiasm. But it was only a matter of time before their ways parted: “Farocki comes from Eisenstein, and I come from Rossellini. He is very fond of montage, I am more interested in life”. Although they are both exploring a critical-essayistic perspective, Bitomsky considers documentary film as an instrument for articulation rather than for deconstruction. So, each film he has been making since the 1970’s provides some sort of map, its routes leading us through unruly territories, covering themes such as memory, history, technology and image culture. In this fourth installment of the DISSENT ! series a selection of Bitomsky’s films will serve as the starting point for a conversation on cinema, documentary practice, image and reality.

Before the talk, on March 28th, we’ll be screening

Hartmut Bitomsky & Heiner Mühlenbrock, Deutschlandbilder

1983-84, 35mm, b/w, German with English subtitles, 60′

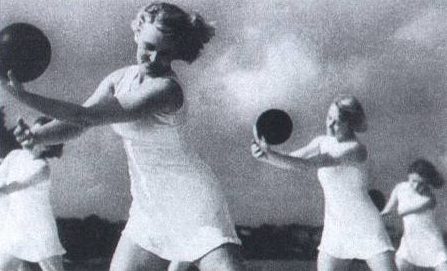

“The film is composed of excerpts from more than 30 documentary films that were made and shown in the period between 1933 and 1945. The documentary films present a clean and self-confident Germany and a people of nature lovers, who respect its traditions, is devoted to progress and has an appreciation for beauty. This was something the Nazis particularly liked; they had a pronounced need for beauty. They loved films and they made ample use of them. Most of the films deal with work, leisure and work again. They indulge in a certain kind of populism, one that casts a look of understanding at the simple man. In this way they function like a reversed plebiscite: the regime confirms its people because they show themselves to be devoted and able and because they participate in everything with creative enthusiasm. Today, however, we must ask ourselves what these films can still tell us. They are profoundly hypocritical, and their intention is to conceal which function has been assigned to them. The more they intend to show, the more they seem to need to keep secret. What can be studied in the films is how film pictures are managed: how they are engaged and turned into instruments, how they are arranged and edited, how commentary and sound is added to them, and how they were taken and used. The Nazi film-makers took great pains to do this. Like advertising strategists, they wanted to seduce. The films and their pictures are like masks that show one face and at the same time cover another. Pictures were taken from reality served to hide reality. Kracauer wrote about this that “The Nazis falsified reality just like Potemkim; instead of cardboard, however, they used life itself to build imaginary villages.” (HB)

DISSENT ! is an initiative of Argos, Auguste Orts and Courtisane, in the framework of the research project “Figures of Dissent” (KASK/Hogent), with support of VG & VGC. The visit of Hartmut Bitomsky is supported by Galeries and Goethe-Institut Brussels.

Also read ‘The documentary world by Hartmut Bitomsky.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

About DISSENT!

How can the relation between cinema and politics be thought today? Between a cinema of politics and a politics of cinema, between politics as subject and as practice, between form and content? From Vertov’s cinematographic communism to the Dardenne brothers’ social realism, from Straub-Huillet’s Brechtian dialectics to the aesthetic-emancipatory figures of Pedro Costa, from Guy Debord’s radical anti-cinema to the mainstream pamphlets of Oliver Stone, the quest for cinematographic representations of political resistance has taken many different forms and strategies over the course of a century. The multiple choices and pathways that have gradually been adopted, constantly clash with the relationship between theory and practice, representation and action, awareness and mobilization, experience and change. Is cinema today regaining some of its old forces and promises? Are we once again confronted with the questions that Serge Daney asked a few decades ago? As the French film critic wrote: “How can political statements be presented cinematographically? And how can they be made positive?”. These issues are central in a series of conversations in which contemporary perspectives on the relationship between cinema and politics are explored.