5 December 2014 20:00, Bozar Cinema Brussels.

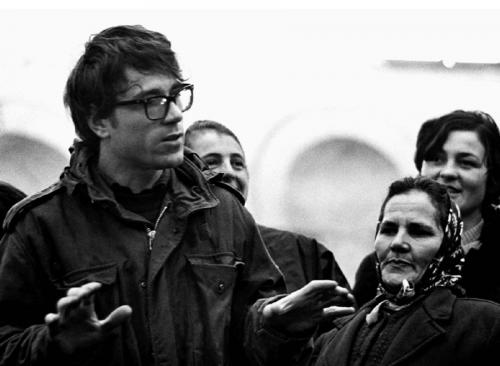

Eric Baudelaire in conversation with Stoffel Debuysere, preceded by a screening of ‘Letters to Max’ (2014, 103’)

“My work is definitely more on the side of asking questions than affirming possibilities of solutions, but then you can probably push that a little further and say that the act of asking questions can be the premisse of some form of possible decision on a course forward, and that is definitely the place I would consider myself in.”

When Eric Baudelaire sent his first letter to Maxim Gvinjia, former Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Abkhazia, he was sure it would come straight back with a notice saying “destination unknown”. Because Abkhazia does not exist, at least not according to the United Nations and the majority of the world’s governments: it seceded from Georgia during a civil war in 1992-93, but its status remains in limbo, caught in a web of geopolitical interests, ethnic tensions and political unrest. However, the letter did actually arrive, marking the beginning of a long exchange which eventually shaped the fabric of Letters to Max: 74 letters sent over as many days, to which Max responded by recording his comments onto tape. The film became the chronicle of a close friendship, intertwined with the particular history of a stateless state, a place that is both real and imagined. Just like in his previous film works, notably The Anabasis… (2011) and The Ugly One (2013), both made in collaboration with Masao Adachi, filmmaker and former member of the Japanese Red Army movement, Baudelaire’s new film is grounded in a process of interchange and discovery, a process that ineluctably leads to unknown destinations, picking up traces of contested histories and unresolved questions on the way. But in any given space of contestation and invention there is no discovery without a sense of confusion and no interchange without a degree of disagreement. So what forms of cinematic perception and interpretation can be constructed as result of this uncertain hovering between different perspectives and sensibilities? How to find a position between refusal and fraternity? How to define the “point of view” of who or what is inbetween? And what does this enigmatic notion of “point of view” still mean after all, after having done its duty both in the service of Bazinian humanism and of Brechtian verfremdung, after having referred to both the gaze of the filmmaker and the blind spot of ideology, both to the position of the author and what it conceals. What can it possibly mean in today’s cinematic landscape, now that it finds itself permeated with a tendency to either hide behind an adherence to “facts… nothing but the facts” or dwell in a borderless sphere of indefinite ambiguity?

DISSENT ! is an initiative of Argos, Auguste Orts and Courtisane, in the framework of the research project “Figures of Dissent” (KASK/Hogent), with support of VG.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

About DISSENT!

How can the relation between cinema and politics be thought today? Between a cinema of politics and a politics of cinema, between politics as subject and as practice, between form and content? From Vertov’s cinematographic communism to the Dardenne brothers’ social realism, from Straub-Huillet’s Brechtian dialectics to the aesthetic-emancipatory figures of Pedro Costa, from Guy Debord’s radical anti-cinema to the mainstream pamphlets of Oliver Stone, the quest for cinematographic representations of political resistance has taken many different forms and strategies over the course of a century. The multiple choices and pathways that have gradually been adopted, constantly clash with the relationship between theory and practice, representation and action, awareness and mobilization, experience and change. Is cinema today regaining some of its old forces and promises? Are we once again confronted with the questions that Serge Daney asked a few decades ago? As the French film critic wrote: “How can political statements be presented cinematographically? And how can they be made positive?”. These issues are central in a series of conversations in which contemporary perspectives on the relationship between cinema and politics are explored.